The ability of financial services firms to transfer or re-register customer assets to another organisation is a lesser known, but a vital part of how modern consumer finance should work. A transfer involves the movement of cash realised by selling the assets to a different intermediary or platform, while re-registration – also known as an in specie or stock transfer – is the process of transferring funds or shares without selling the underlying investment.

The amount of money held in funds by UK savers via investment platforms has soared in recent years. According to a 2017 market study by the FCA, platform assets held through fund brokers in the UK hit £592bn in 2016, up from £108bn in 2008.

The UK government also reports an increase in the total value of stocks and shares in ISAs from 2012 to 2018, increasing from £189bn to £337bn, while the innovative finance ISA has risen from £46m in 2012 to £366m in 2018.

And Origo, a not-for-profit fintech company owned by 14 of the UK’s largest life and pension companies, says that its Options Transfers business has transferred more than £150bn worth of pensions (including SIPPs and workplace pensions) and ISAs since it launched in 2008. Origo is widely used among life insurers and self-invested personal pension (SIPP) administrators, with 90 or more brands using the service to complete cash pension transfers electronically.

The automatic pension enrolment programme has seen more than 9.5 million people join a workplace scheme between October 2012 and May 2018, according to the Department for Work and Pensions. The 2015 freedom and choice reforms that gave pensions savers access to an unprecedented number of investment options will also push up the number of asset transfers and re-registrations taking place. According to The Pensions Regulator (TPR), direct benefit pension schemes reported approximately 72,700 transfers out between April 2017 and March 2018, worth a total value of US$14.3bn. However, taking into account non-responses, TPR estimates the true number at 100,000.

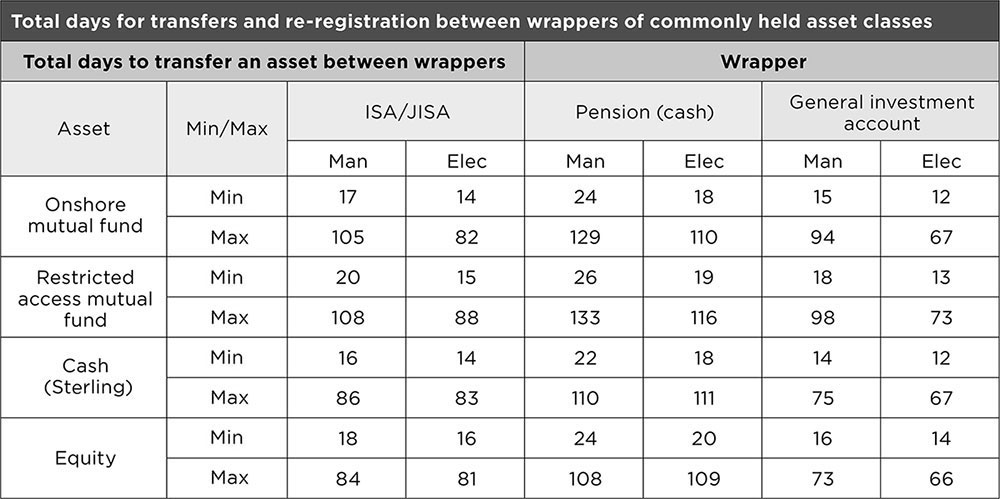

But the speed and efficiency of these procedures have not kept pace with the increase in demand. Transfers often take up to 100 business days and as many as 133 business days – or six calendar months, according to the 2016 Improving pension and investment transfers and re-registrations consultation paper, issued by ten financial services sector bodies, including the Association of British Insurers (ABI) and the Association of Member-Directed Pension Schemes.

Source: The 2016 Improving pension and investment transfers and re-registrations consultation paper. Note: ‘min’ means minimum total days to transfer an asset, ‘max’ means maximum, ‘man’ means manual processing, ‘elec’ means electronic processing.

There are clear areas of potential customer detriment where re-registration is either not enabled or is slow and inefficient. These include risks from being out of the market, potential tax liabilities, and lost investment opportunities.

The current regulations set out by the FCA in its

Conduct of Business Sourcebook stipulate only that a firm must execute the client’s request for a transfer “within a reasonable time and in an efficient manner”.

The maximum time periods for transfers in trust-based schemes are set out in legislation. For members of trust-based defined contribution (DC) schemes, the transfer must generally take place within six months from the start of the transfer process, according to the

Pension Schemes Act 1993.

The Pensions Regulator also says fund trustees must ensure transfers are processed

“promptly and accurately”, but adds that there is a balance to be struck between prompt processing and adequate due diligence.

Following discussions with the FCA in March 2016, the main trade bodies representing the major parts of the investment and pension sector agreed to undertake a review of the effectiveness of processes for transferring and re-registering assets between providers. As well as the ABI, it includes the Association of Member Directed Pension Schemes, the Investment Association, the Pensions Administration Standards Association, the Pension and Lifetime Savings Association, the Personal Investment Management and Financial Advice Association, the Society of Pension Professionals, the Tax Incentivised Savings Association, UK Finance, and the UK Platform Group.

On the basis of that consultation, the Transfers and Re-registration Industry Group (TRIG) drafted a sector-wide

framework, which its member organisations have endorsed and encouraged their members to adopt.

Good practice

Rob Yuille, head of retirement at the ABI, says TRIG concentrates on setting out good practice standards to ensure the end-to-end process and each step is improved for the consumer.

“While we recognise the sector has done a lot to improve transfers, both in terms of speed and process, that is not necessarily done consistently, and there have been different solutions for different parts of the sector,” he says.

The framework sets out strict timelines for the transfer process and lays down standards on communications with clients. The keystone is maximum limits on the time taken to complete a transfer from end to end.

For transfers between two counterparties involving cash pensions, companies should take no more than ten business days from when the acquiring firm receives a completed instruction from the client to the receipt of the transferred funds. For occupational pension scheme transfers between two counterparties, where the holdings are transferred rather than sold, the process should take 15 business days.

For these transfers – and for all others, such as ISAs – the framework envisages organisations adopt a maximum standard of two full business days for completing each step in a transfer and re-registration. An example of a step is the acquirer receiving, validating and processing a client transfer, and sending an electronic discovery request to the ceding party (the fund that currently holds the investment). For example, ISAs can be transferred either electronically (using the TeX electronic re-registration process) or manually, whereas pension cash transfers are transferred electronically through an electronic transfer service, such as Origo Options Transfer service (although other services are available).

The mechanics of an asset transfer

If an investor wants to transfer the assets they hold in an investment product such as shares and bonds to another provider, the ceding portfolio manager and acquiring manager will need to go through eight steps:

Step 1: The manager of the fund acquiring the assets sends a discovery request to the fund currently holding the assets to confirm what they currently hold.

Step 2: The fund that currently holds the assets sends over a valuation listing the assets held by the customer and their identifying numbers (known as the International securities identification number or ISIN).

Step 3: The acquiring managers then instructs the ceding manager whether to encash the assets (for a cash transfer) or re-register them, depending on the client’s instructions.

Step 4: The ceding manager then sells the assets and/or re-registers them.

Step 5: Both managers use the CREST securities depositary to settle exchange-traded assets such as shares and bonds. For mutual funds, the ceding manager sends an electronic message to the other manager. This usually takes two days.

Step 6: Transactions complete in CREST, transferring the assets from the ceding to the acquiring manager.

Step 7: The ceding manager completes the transfer on the client account and sends an electronic completion message to the acquirer.

Step 8: The acquiring manager completes the transfer into their client’s account.

Most steps require a written communication and any steps that are done by post will add at least one extra day. For example, if the account is held inside a tax wrapper such as an ISA, the ceding party will need to send the ISA declaration manually.

In order to ensure that customers and consumer groups can see that these deadlines are implemented, TRIG acknowledges there needs to be an improvement in data collection so that it is clear what end-to-end transfer and re-registration times are for different types of operation, and where any failures are occurring.

“By definition, we are speaking to the firms that are engaging and that want to do this properly so would like the help of the FCA and Department for Work and Pensions to take stock of where we are with each type of transfer, how long it takes, and which types of firms are most likely to hold it up,” Rob says.

Richard Stone, chief executive at The Share Centre, which has acquired books of clients from Invesco, Janus Henderson and more recently Beaufort Securities, says the transfer of customer accounts and assets in such a situation is relatively straightforward.

However, he adds that where a client decides to move from one broker to another, the transfer can be more complex. It has to be triggered by the customer selecting a new broker and instructing that broker to request the transfer from the existing provider. The transfer process can then take some time depending on the systems used – different brokers typically use different systems – and the assets involved. The TRIG framework acknowledges this, saying that if there are multiple counterparties in a transfer process, an end-to-end standard would mean that firms would be held accountable for the failures of others in the process.

“The objectives of TRIG and the FCA to simplify and streamline the transfers process should be welcomed by the sector and by customers,” Richard says. “They should help set standards for transfers and improve the timeliness of the process in some cases, although issues such as share classes unique to specific platforms may continue to add time to that process.” In many cases these can be overcome by going through the processes and jumping the hurdles although of course this will add to the time and cost of the whole procedure. A survey for the FCA carried out for its June report finds that about a quarter of advisers said it is difficult or very difficult to move investments from one platform to another. Barriers include: the time of the transfer process; costs and charges; and specific product issues such as additional internal processes involved with a SIPP. The TRIG framework echoes that, saying that where an acquiring party cannot hold a particular asset, then it will have to ask the ceding party to sell the asset and send funds to the acquiring party. This may add time to the process.

Stop the clock

Many firms are already meeting these standards, according to Rob at the ABI. One way of achieving the two-day target will be for firms to ensure that any processes that are done manually, such as by post, are done electronically, he says.

There will be some circumstances where firms find it is not possible to complete a step in this timescale. The TRIG framework makes clear that while there can be no exemptions from the standard, counterparties could be allowed to ‘stop the clock’ in certain circumstances.

A precise list has not been agreed, but the framework gives examples of legislation over ‘cooling off periods’, if there are unpaid fees, and if there is unavoidable disruption beyond the counterparty’s control. If there is concern that a transfer might be a scam, Rob says this would increase the amount of due diligence that the firm passing over the asset would need to do to. “A firm won’t be judged for slowing down a transfer if there is a legitimate reason,” he says.

TRIG has also responded to the FCA’s demand that the firm taking over management for the asset provides clear communication to customers at the start of the switching process, detailing the transfer process, timelines and giving them a point of contact if they have any questions or wish to complain.

Under the framework, customers should be given an indication of the likely timeframe, a summary of any relevant potential causes of delays, and details of whom they can contact if something goes wrong.

One controversial area that is still open to debate is the level of charges that advisers can impose for transferring accounts, known more commonly as exit fees. The FCA

stated in July 2018 that it was considering banning exit fees. The news knocked the price of shares in listed fund managers, such as Hargreaves Lansdown, whose share price fell 4% on 28 June 2018, although that particular loss was recovered soon after.

In terms of overall costs, Rob says that the actual costs “vary widely” from firm to firm. It is true that a significant proportion of cost in any pension transfer is employee time in processing the transfer (though many firms are automating these processes) and performing due diligence on the intended receiving scheme.

In its July 2018 report, the FCA said that many advisers had said they charged additional advice fees for switching platforms because it is a full advice event which requires them to produce a suitability report. The FCA said it was considering whether to issue more guidance to clarify its expectations for how advisers should charge for switching platforms. “We recognise advisers need to be fairly paid for their work,” the FCA report said. “But it is not clear to us why meeting suitability requirements to switch platforms should outweigh the benefits of switching platforms.”

Rob says TRIG, as a sector initiative, could not agree an approach to charges and pricing because doing so would breach competition law. “The ABI will be responding to the FCA and we’d expect some other associations to do so as well.”

Next steps

The FCA says it expects the sector to implement changes in three key areas – end-to-end standards for transfer and re-registration times; clear communication to customers; and publication of data on transfer times – before it publishes its final report in the first quarter of 2019.

“If we are not satisfied with the progress that has been made by that point, we will consider the merits of taking further action to improve the switching process. Our potential options include remedies to shine a light on firms’ switching times and mandating timelines for the process.”

TRIG says that the framework is voluntary as its member associations, which include bodies such as the ABI and the Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association, are not in a position to compel, supervise and enforce against their members.

Rob says the TRIG framework provides standards for good practice that would require support from the whole sector. “It is a slightly different way of doing things but it’s important we press ahead, otherwise the FCA says it will act.”

Seen a blog, news story or discussion online that you think might interest CISI members? Email bethan.rees@wardour.co.uk.