Mervyn King was Governor of the Bank of England (BoE) from 2003 to 2013 and witnessed first-hand the build up to, and consequences of, the 2008 financial crisis. In his scholarly and insightful book, The end of alchemy: money, banking and the future of the global economy, he shares his thoughts on what went wrong and why, and how things might be fixed so as not to occur again.

In the introduction, King says: “The growth of indebtedness, the failure of banks, the recession that followed, were all signs of much deeper problems in our financial and economic system. Unless we go back to the underlying causes we will never understand what happened and will be unable to prevent a repetition and help our economies truly recover.”

He goes on: “This book looks at the big questions raised by the depressing regularity of crises in our system of money and banking. Why do they occur? Why are they so costly in terms of lost jobs and production? And what can we do to prevent them? It also examines new ideas that suggest answers.”

There has been a proliferation of books written about the crisis. Most focus on the role of the banks and the massive growth of complex financial instruments. King’s book is much broader and much more thoughtful. While he does not seek to blame any individuals and institutions, he acknowledges that there were clear policy errors. Most he puts down to the terms of the remit or the inadequacies of the economic models used by banks and central banks.

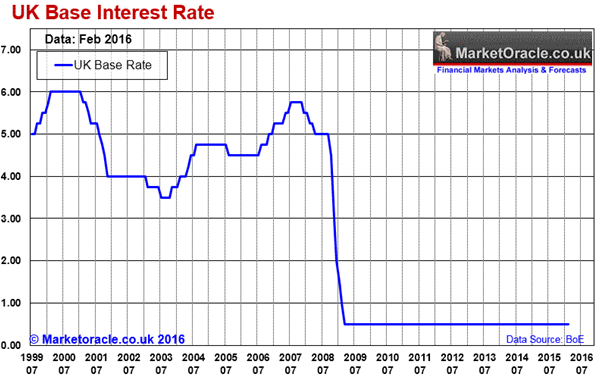

Symptom, not causeUnlike most of the other books written about the crash, King sees the failure and the failings of the banking system as a symptom of the crisis, not the cause. The cause he puts down to growing disequilibrium in the global economy, which built up after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. A simplified version of his thesis is: China and Germany became successful exporting nations, running up substantial surpluses that are invested overseas, driving down interest rates in the UK, US and Europe, and allowing an unsustainable growth in consumer debt to finance today’s purchases with tomorrow’s income. The Monetary Policy Committee of the BoE debated this unsustainable imbalance in the pattern of demand as early as the late 1990s, but decided not to raise interest rates, as this might have derailed the otherwise steady growth and inflation. The simple cure for this imbalance is investment in China and Germany to produce goods and services to meet domestic demand, rather than to support the export sector. The opposite is the case in the US, UK and parts of Europe.

After a truly fascinating and educational analysis of economic theory and practice, King determines that little has changed since the crisis, and continuation of these same policies will lead to another crisis in time. But in the meantime, he suggests: “With interest rates close to zero, and fiscal policy constrained by high government debt, the objective of economic policy in a growing number of countries is to lower the exchange rate … [which would] ultimately [be] a zero-sum game as countries try to steal demand from each other.”

Again, unlike many of the other books on the subject, he articulates a logical and understandable alternative to the current central and commercial banking model, including a return to a complete division between investment and retail banking. Unfortunately, this alternative is unlikely due to the political strength of the banking lobby. While a lot has been done to improve regulation of the banks since the crisis, he concludes they still need more equity and less leverage.

A chequered history King cites many of the paths the economic world is on that lead to failure. For example, he says that “monetary unions have a chequered history” with little chance of success without political union, and without that, the euro will likely fragment. No matter how much austerity the Greeks are obliged to go through to be allowed to roll over their debt, the level is unsustainable and they will default at some stage. The Chinese financial sector is not thought to be in great shape either.

The end of alchemy: money, banking and the future of the global economy, by Mervyn King.

Published by Little, Brown Book Group, 3 March 2016I found this an illuminating book about how the world works. However, I would have liked to learn more about two aspects. Firstly, how governments and banks interact to determine who does what in terms of fiscal and monetary policy and secondly, who regulated the banking sector and how, both before and after the crisis. The book, I thought, was surprisingly quiet on both subjects.

Readers of this book will gain valuable insights into economic theory and practice. I urge you to be one of them. Certainly, I feel better educated having read it. Whether collectively we are any the wiser as a result remains to be seen.

A word on fiscal and monetary policy

There are two broad drivers of public economic policy: fiscal policy and monetary policy. Fiscal policy encompasses government taxation and spending. Monetary policy seeks to control the cost and supply of money in the economy and is controlled by the central bank – in the UK, the BoE. Most central banks have stable inflation as their target priority, which they seek to control by lowering rates when inflation is deemed too low and the reverse when inflation is deemed too high. Central banks can also tighten or loosen monetary policy by selling or buying financial instruments, such as government bonds.

After the financial crisis in 2008, when the global economy fell into severe recession, governments around the world were to varying degrees unable or unwilling to cut taxes or raise spending due to already high government debt and deficits. As fiscal policy was not an option, it was left to central banks – including the BoE, the US Federal Reserve and, more recently, the Bank of Japan and European Central Bank – to embark on a massive monetary experiment. First, they cut policy interest rates to zero and second, they started an unprecedented programme of buying back government bonds, now termed quantitative easing or QE.

Six years and many hundreds of billions of buy-backs later, the economic recovery remains anaemic with many of the imbalances evident before the crisis now even more exaggerated. This has led critical economic and stock market commentators to question both the efficacy and the wisdom of this exceptional monetary experiment. Others have called for yet more ‘unconventional’ monetary measures, including 'helicopter money', the banning of cash or sovereign debt forgiveness.