With the Olympic Games over, the global spotlight has now moved away from Brazil – which may have put on a show at the time, but behind the scenes was in chaos, struggling with political scandals and economic turmoil.

Two months before the games started, Rio de Janeiro declared a “state of public calamity in financial administration”. Costs had spiralled out of control and the oil rich region was suffering further due to low oil prices. On the national stage, the president, Dilma Rousseff, was suspended pending hearings on her impeachment. Combined with a failure to handle the Zika virus, murky green water in the diving pool was the least of the organisers’ problems.

The games might have concluded somewhat successfully, but the political crisis has been tougher to resolve. Rousseff has been formally impeached, accused of cooking the books to make the Brazilian economy appear healthier than it was ahead of elections. The new president Michel Temer has approval ratings even lower than his predecessor, with between 30% and 50% of the population regarding him as ‘bad’ or ‘awful’, depending on which state you ask. Temer now has the unenviable job of trying to fix a dysfunctional economy and mend a fractured electorate.

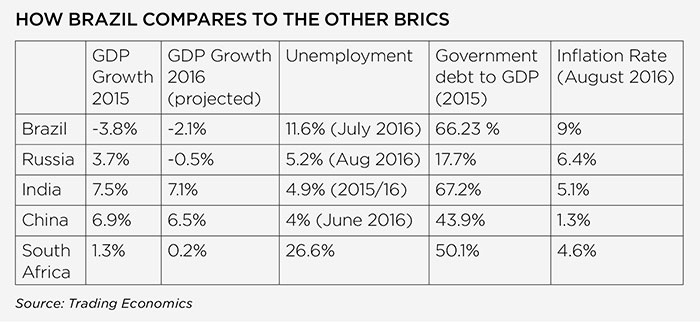

New challengesThe country is struggling with an enormous budget deficit and is expected to contract 4.3% this year, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, which is a significant drop from last year’s 3.8% contraction. According to SOAS Development Studies Professor Alfredo Saad Filho, author of

Brazil: the débâcle of the PT and the rise of the ‘new right’, the new Government has a few difficulties ahead. “There is no economic driver in the economy,” he explains. “Brazil went through a process of deindustrialisation over the past thirty years. Successive governments have adopted a policy of pursuing easy commercial opportunities rather than more articulate ones, or ones that worked while conditions, such as strong commodities prices, were favourable. But the international crisis left Brazil without alternatives.

“Since 2011 the Government has struggled to attract domestic investment because of its economic policy. This strike in investments effectively destabilised the Rousseff Government, and eventually succeeded in removing it, according to FIESP (Sao Paulo State Industry Federation).”

It could be argued that the crisis should have been predicted: the boom Brazil experienced at the beginning of the century was fuelled by high commodity prices. At the same time, very few structural reforms or investments in vital infrastructure were made while there was money pouring into the country. It can also be argued that Rousseff’s economic policy was inadequate since the early days of her first term as president. As early as 2011, economists were raising flags: economics reporter Beatriz Ferrari wrote in leading Brazilian weekly news magazine

Veja that year that “the Government does not appear to know – or agree with – the importance of the preservation of the macroeconomic tripod [substantial primary surplus, inflation targeting and floating exchange rate].”

"This knocked even more demand from the economy. In a context of weak commodity prices and no investment in Petrobras, the country started to contract rapidly, destroying that last driver: consumer spending"Brazil’s current crisis is institutional rather than the result of the natural peaks and troughs of an economic cycle – caused by the former Government’s poor management and an inability to respond to external pressures. Investors picked up on the red flags and swiftly exited the market.

As the crisis deepened, public investment dropped. “Since 2014, the Government has followed an orthodox strategy of economic adjustment to get the fiscal deficit under control by cutting costs,” says Saad Filho. “This knocked even more demand from the economy. In a context of weak commodity prices and no investment in Petrobras [the part state-owned oil company], the country started to contract rapidly, destroying that last driver: consumer spending.” Families stopped taking new debt and unemployment grew, leading the economy to complete stagnation.

This is the worst recession Brazil has faced in over 80 years. Indeed, in the mid-2000s and for much of the left-wing Workers’ Party rule under former president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, the country grew at unprecedented levels, coasting on high commodities prices. Under Lula the percentage of the population living under the World Bank’s poverty line dropped from 12.3% in 2002 to 4.8% in 2013.

During the same period, however, a series of corruption scandals involving elected politicians from many mainstream parties, including the governing Worker’s Party, have come to the fore. This has further eroded public confidence in the political system and engendered a deep dissatisfaction, particularly among wealthier portions of the population. Rousseff’s impeachment has done little to assuage the electorate, which remains deeply divided. Supporters of Rousseff and the Workers’ Party insist allegations against her and Lula’s involvement in corruption scandals are a smear campaign aimed at removing the leftist party from power and destroying their chances in the upcoming elections in 2018.

Meanwhile, Rouseff’s detractors have latched on to her mishandling of the accounts – something she insists all former presidents have done before – as just further proof of the corrupt nature of her Government, and lay the blame for the struggling economy on her. Mr Temer, though elected as vice-president two years ago as part of a coalition front, is a centre-right politician and will take a different approach to economic and social issues. That will hardly prove popular with the electorate, who chose a leftist government.

Seeds of change?In early September, the new Government announced a packaged of measures entitled ‘Grow’, aimed at getting the economy moving again. It largely consists of a rapid plan to privatise some existing infrastructure and offer new contracts to private firms for a variety of projects ranging from building new roads to developing mining assets. “The state cannot do it all,” Temer said as he announced the measures.

US$55bn

The level FDI is expected to drop to during 2016

Earlier in the year, Temer, while still interim president, signed a law that allows for full foreign control of new oil fields. Brazil has vast reserves of potentially lucrative deep-water fields along the coast. Previously, foreign companies hoping to get involved in the exploration would have to play second fiddle to Petrobras, as it had to be the main operator and own 30% minimum of any fields, by law.

Petrobras has been at the centre of one of the biggest corruption scandals of the decade, and has been left in a debilitated state. By removing the obligation of Petrobras to be involved in every drill, Temer is hoping to kill two birds with one stone: to stop Petrobras haemorrhaging money in projects it can scarcely afford, without losing out on royalties, and increasing foreign direct investment (FDI) in the country. In 2011, FDI had shot up to US$101bn as deep-water wells began to be explored. It is expected to drop to US$55bn this year, according to the Banco Central do Brasil, the central bank. Temer is hoping that by opening up the oil market he will slow this dive. “Brazil is still reliant on FDI in order to fund domestic consumption,” says Edward Glossop, Latin America Economist at economic research company Capital Economics. “However, the country is less reliant on foreign capital to fund economic growth than it once was (in the commodities boom, for example). This is because its current account deficit has narrowed sharply since then. That said, of course, more FDI would be positive for growth.”

None of his new measures are likely to be popular with an electorate still in support of the impeached president and her successor. It doesn’t help that so many elected officials are involved in one corruption scandal or another. Eduardo Cunha, the man credited with orchestrating Rousseff’s impeachment while speaker of the house, was himself impeached from the role in early September after investigations uncovered $52m hidden in a Swiss bank account. Cunha was a vital ally of Temer.

"Brazil is still reliant on FDI in order to fund domestic consumption"

Beyond regaining the confidence of the market, Temer will have to undertake reforms that successive previous governments have failed to. Brazil needs urgent tax reform – at the moment each state dictates its own tax regime, in a complex and cumbersome system that involves a variety of different taxes and tariffs. Because states rely on these levies for income, any attempt to consolidate the tax system is likely to face resistance. Brazil’s labour laws also need reforming, as they are are largely complicated and archaic in their scope and intention. It is expensive to hire, fire and retain skilled staff, which causes companies to rely on informal workers, which in turn causes a shortfall in tax revenues for the state. Finally, Brazil needs to become more open for business, which the new president seems ready and willing to embrace.

However, without meaningful political reform, there is little hope that Brazil will be able to return to full growth and sustain it in the long term. It will be an uphill climb to get investors, foreign and domestic, back on board. “One factor that should entice investors back over time is a weaker real – this underlines the importance of keeping the real weak (in order to stimulate both FDI and exports),” says Glossop. “More fundamentally though, concrete improvements in the monetary position (for example the passing of the federal spending cap, introduction of pension reform to congress) are needed to help to build confidence and stimulate further FDI.

“At some point the economy hits rock bottom,” says Saad Filho, “and my intuition says that has happened, but the tendency is for growth to be protracted in the short term. This was happening in the early 2000s, and if it returns to that level of growth and employment, Brazil will have lost a decade. That is a shame.”