Mauro Tortone, Chartered MCSI

Mauro is a director and adviser at P27, a business advisory firm focused on financial services and technology.

He is also a CISI external specialist (capital markets & corporate finance) and mentor.

He sat on the CISI Corporate Finance Forum committee for over ten years.

Mauro has over 25 years of experience working for investment banks such as UBS and Deutsche Bank and smaller firms in the EU, the US, and Asia.

He is an alumnus of London Business School (Investment Management Programme) and Henley (MBA).

Mauro can be contacted at mauro.tortone@p27.network

The post-Covid, deglobalising, climate-challenged world is forcing all businesses to navigate a sea of change. Sometimes, change means growth. Sometimes, it means evolution. For sustainable change, there are certain value creation considerations that business leaders need to be aware of and act upon. Growth, for example, can destroy value and be bad for people and the planet.

Traditionally, the job of business leaders is to increase the value of the business over time, for as long as possible. Today’s valuations should include the traditional factors such as sales, earnings, and investments, but also, through consideration of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors, reflect the transition from shareholder to stakeholder capitalism that is taking place alongside the move to a greener and fairer economy.

Businesses need to be agile, adapting to the fast-changing world around them. In this article, I propose a model for value creation in the long term based on three pillars, focusing primarily on one: the strategic integration of ESG factors in a business.

Traditional long-term drivers of value

Traditionally, the primary long-term drivers of shareholder value include sales, earnings, investments (projects), planning period, and cost of capital. However, most businesses are good at extracting value from operations, but not from projects (change), where a lot of value should be coming from – especially if a business is at an earlier stage.

Businesses are expected to increase their value, over time, and to create value for their owners (i.e. shareholders). To do so, they allocate their scarce resources to the most promising operations and projects.

Big banks have two organisational components to deal with operations and projects: run-the-bank and change-the-bank. The former is there to make sure the bank makes money now. The latter is there to ensure that the bank will make money in the future.

Other large businesses have similar arrangements. Smaller businesses often do not have much structure around projects.

From my research and experience, I learned that projects have a significant impact on value. Typically, project appraisal (financial considerations) and project portfolio prioritisation (strategic alignment) are the two areas in which businesses need to improve the most.

Corporate life cycle

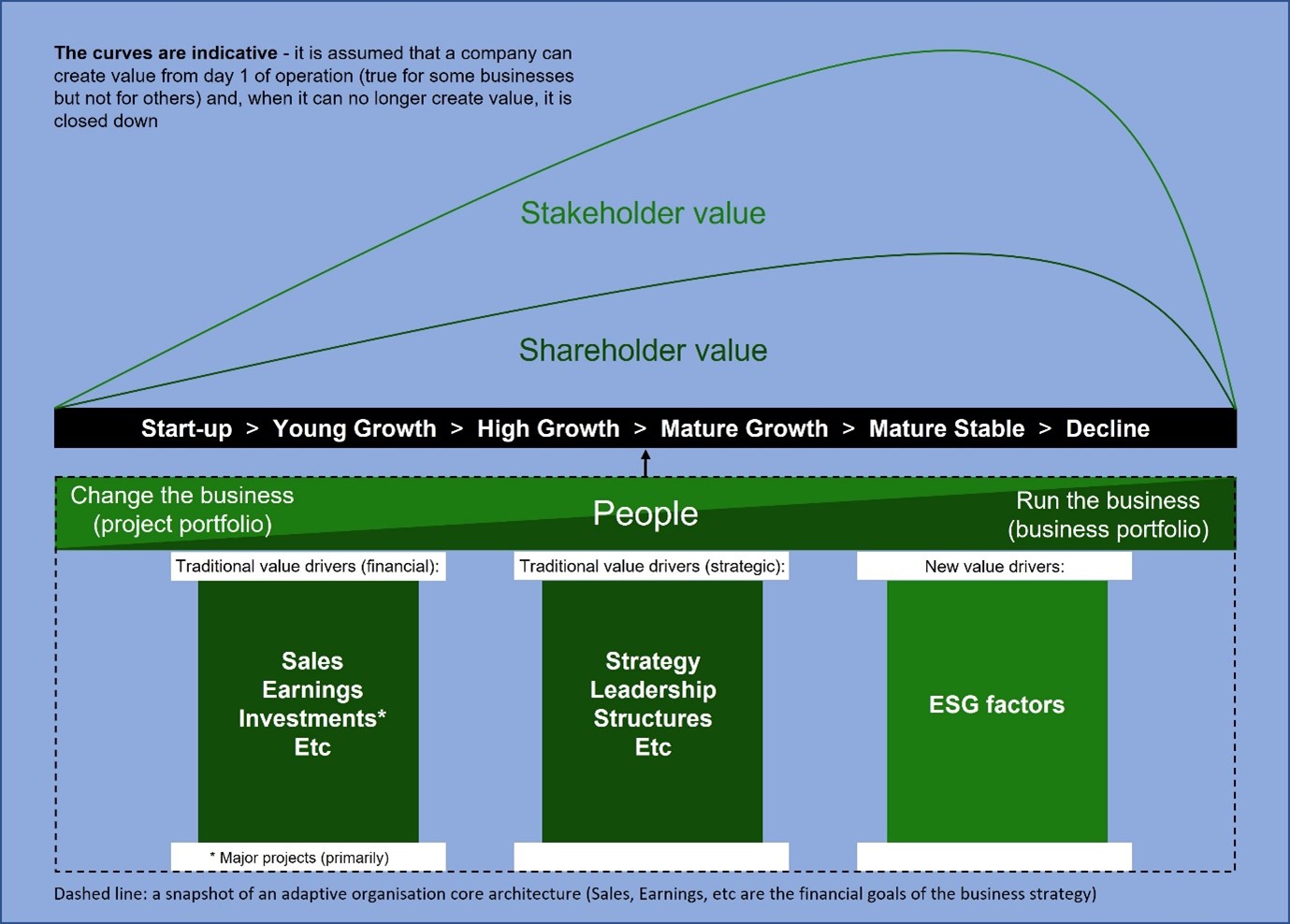

According to Aswath Damodaran, professor at NYU Stern, the corporate life cycle has six stages: start-up, young growth, high growth, mature growth, mature stable, and decline. Businesses do not like to get old, but ageing is inevitable and requires a change of focus, otherwise their life cycle will be shorter. A business valuation should reflect this.

A lot of value is destroyed by businesses not acting their age. Often young companies try to act old and old ones try to act young – perhaps following the advice of management consultants and investment bankers.

To be fair to business leaders, consultants, and bankers (I am a founder, consultant and former banker), Professor Damodaran’s guidance on stage and focus is useful, but it is not always straightforward to get right.

Nevertheless, it is important that business leaders make an honest assessment, communicate it to stakeholders and act accordingly.

Scaling problem

According to Geoffrey West of the Santa Fe Institute, most companies disappear after ten years. Only a few make it over 100 years, with even fewer making it over 200 years. The longest surviving companies are relatively modest in size and are highly specialised, operating in niche markets.

To scale up (i.e. grow in a proportional and profitable way, achieving more efficiency, market share and earnings), companies add rules, regulations, and protocols. At the expense of innovation: their dimensionality continually contracts, eventually stagnating. Dimensionality here means the space of opportunity, functions, and jobs.

Unlike companies, people, or organisms, cities do not seem to die. I agree with West – companies should look at more open organisational models, considering how cities are run. But I would add that the overall business (or corporate) strategy and leadership also play a role in determining the ability of a business to scale and prosper over time.

ESG factors

Today, investors around the world increasingly want to invest in sustainable businesses. And regulators in most countries, led by the EU, are preparing new rules requiring businesses to provide better ESG disclosures, protecting investors from greenwashing.

The basics of ESG:

- The E factor includes the use of energy, water, and other resources of your business

- The S factor includes relations with all the stakeholders of your business

- The G factor includes your ability to prepare for risks and opportunities

Businesses need to integrate the ESG factors into their strategy, then implement the actions that improve them as part of the overall strategy with the support of every part of the organisation, and finally report progress to stakeholders.

Sustainable change

I believe that to scale up and extend the corporate life cycle, i.e. to change sustainably, adaptive organisations need to manage:

- The traditional financial drivers of value, such as sales, earnings and investments to increase shareholder value over time, rather than short-term profit

- The traditional strategic drivers of value, such as the non-financial goals, leadership, and structures to maintain an innovative organisation

- The new drivers of value – the ESG factors to increase stakeholder value over time

Adaptive organisations: the three pillars of sustainable change

Source: P27

How to integrate ESG into your business

Integrating the ESG factors into your business is a long project. But they will make it easier and cheaper to finance and insure your business and attract talent and partners.

The first step your business should take to start the ESG journey is to task a person or a small team to assess your current ESG state and plan the integration. The assessment should include the ESG policies and metrics that you need (there are many standards to choose from), required data points, UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) you can pursue, and a system for tracking progress. The plan should include the roadmap to get to the ESG state that your investors and other stakeholders want to see in the future.

The person or team could be either from your organisation or external experts. The key is that they must have the full support of the board.

SDGs

The UN SDGs are a collection of 17 interlinked global goals, adopted by all 193 United Nations member states in 2015 as a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure that by 2030 all people enjoy peace and prosperity. They include, for example, no poverty, quality education, gender equality, affordable and clean energy, and responsible consumption and production.

They provide a blueprint that organisations, including businesses of all sizes, can use to implement their ESG policies. Your business does not need to pursue them all, but it can choose those relevant to its stakeholders and that the organisation can deliver. Responsible business and investment will be essential to achieving change through the SDGs.

In addition, the SDGs are also entering financial regulation in the UK, the EU and other jurisdictions.

The High-Level Political Forum (HLPF), a UN platform, reviews the progress of SDGs annually. The UN SDGs report provides an annual overview of the world’s implementation efforts.

Environmental accounting, data and blockchain technology

Regulators and capital markets will increasingly penalise firms ignoring the environmental and social costs. But these are uncertain, inconsistently measured and their negative impact will be felt the most at some point in the future – they are not easy to value. Here is where environmental accounting, data, and blockchain technology can help.

There are many environmental accounting initiatives. One is the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), established in 2021, merging several existing sustainability standards bodies. It sets out how a company discloses sustainability information that may help or hinder a company in creating value.

The ISSB works closely with its older sister organisation, the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB), whose standards are required in over 140 jurisdictions. The International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation oversees both the ISSB and the IASB.

Organisations that want to be sustainable collect ESG data. They include financial institutions that create sustainable portfolios and corporations that report on sustainability performance. They source it internally using proprietary IT systems and third-party platforms.

These organisations use ESG tools that facilitate the rollout of sustainability requirements and progress reporting. These are IT applications that help the executive team identify the policies, standards (metrics) and data they need, which should be country, sector, and organisation specific.

Demand from the financial services sector drove the initial data and tools offerings. Now virtually all sectors require them.

Distributed ledger technology (DLT), known by most people as ‘blockchain’, could bring transparency, integrity, and efficiency. It could better enable organisations to track sustainability data on infrastructure projects. Provided it is using a ‘proof-of-stake’ consensus mechanism (see ‘powering the digital currency machine’ for more information on this), which doesn’t consume any more energy than traditional database solutions, it could also be used to lower the cost to structure, issue and distribute sustainability-linked bonds and other green finance instruments.

Geopolitical risk considerations

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has accelerated the move towards a multipolar world, in physical and digital terms. It will feature independent regional economies where Western-led rules no longer apply in large parts of the world. These rules include ESG.

It is reasonable to expect that this will make it even more difficult to coordinate global responses to challenges such as climate change.

Businesses that want to contribute to making the global financial system more inclusive and the global economy greener should reflect on the impact that recent geopolitical events are likely to have on the transition to a sustainable economy.

Business leaders will need to develop the ability to operate in a multipolar context where regional values and viewpoints must be better understood and respected than in the past. And they will need to adjust the role their business plays and its solutions.

Final thoughts

Change is not easy at any stage of a corporate life cycle, but it gets less easy with age.

Project failure is not a bad thing that must be avoided. It is part of changing the business. Businesses should manage their change portfolio to ensure they have enough stars to deliver not only the expected portfolio return above the cost of capital of the company but also the expected portfolio impact.

The change portfolio must include ESG projects. Because regulators, investors, partners, employees, clients and consumers demand it. And because it is the right thing to do for your business and the planet. Ultimately, ESG factors should become an ongoing business process, for both strategic and compliance purposes.

In the post-Covid, deglobalising, climate-challenged world, the old business mantra ‘grow or die’ should be replaced with ‘change or die’.

Glossary

Cost of capital

The rate of return that a business must earn before making a project worthwhile financially. It includes the cost of debt and equity. And it determines how a company can raise money (through a stock issue, borrowing, or a mix of the two). Investors use it as the discount rate in the discounted cash flow model when valuing a business.

Shareholder capitalism

The traditional form of capitalism in which the interests of one stakeholder, the shareholder, dominate over all others. Businesses operate with the purpose of maximising shareholder value, often at the expense of the other stakeholders and the environment.

Stakeholder capitalism

A system in which corporations serve the interests of all their stakeholders, such as shareholders, customers, suppliers, employees, and local communities. Its supporters believe that this is critical to the long-term success of a business.

Shareholder value

The traditional prime goal of a business, i.e. economic return on capital invested in excess of the cost of capital. Shareholder value equals business value plus marketable securities and investments minus market value of debt and obligations. Where the business value is the value generated by the free cash flows in which all providers of funds have a claim.

Stakeholder value

An alternative prime goal of business, which includes the shareholder value plus the other stakeholder value. The latter is not as easily quantifiable as the former, but there are several models used such as the balanced scorecard (adapted to reflect stakeholder goals for multiple bottom-line performance) and social efficiency.